At a glance

The NSW Women’s Opportunity Fund

Disadvantaged women face a range of economic challenges. One specific challenge, that can be addressed, is the gap in capital available for women who own a viable small business. This policy brief canvasses a proposal for the New South Wales (NSW) Government to create a NSW Women’s Opportunity Fund (“the Fund”).

As a government-owned impact investment fund, which crowds in private capital, the Fund would provide financial products alongside holistic business support and advice to women entrepreneurs and small business owners who belong to disadvantaged groups. The Fund could provide capital in different forms and combinations (e.g., concessional loans, equity investments, grants) as well as facilitate access to a range of additional supports, such as networks and upskilling, to enable women to grow an existing business. Commercial financial institutions, particularly banks, would have strong reasons to participate in the Fund: to connect with potential business clients, while delivering on corporate responsibility objectives.

The Fund would represent a step change in empowering disadvantaged women with small businesses to boost their economic security and create good jobs.

By adopting a social impact investment framework – one which encompasses economic security and good jobs – the Fund would differentiate itself from other sources of finance. In particular, the Fund would have a willingness and capacity to take on risk (for instance, when owners have few or no assets, or lack credit history), and to offer a degree of flexibility to its recipients, that reflects the lived realities of disadvantaged women. Moreover, the Fund would help overcome the human and social barriers to accessing capital, such as language barriers or a lack of social capital. These barriers can lead to an absence of relatable and approachable financing options in the communities where it is needed.

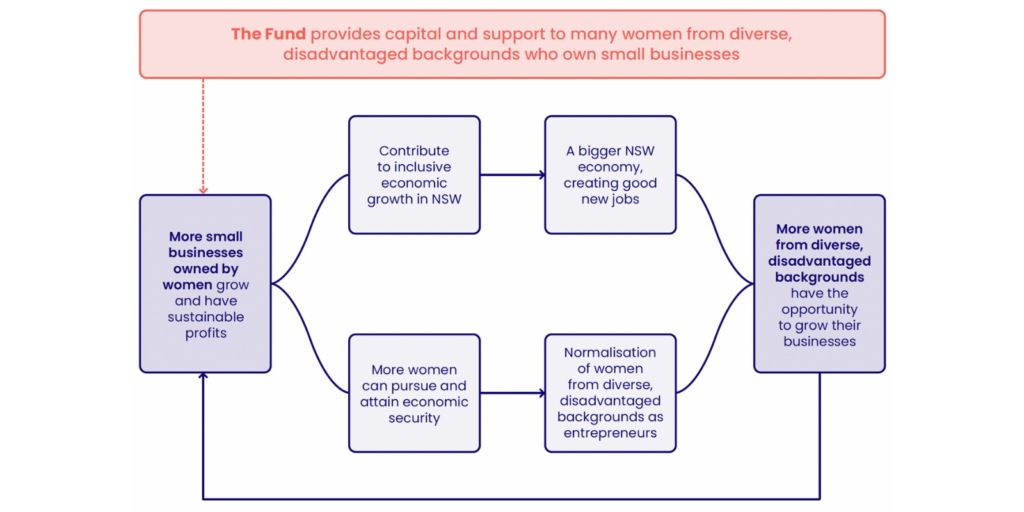

The Fund would aim to expand the ecosystem of successful small businesses owned by women in NSW. It would support a large number of conventional small businesses to scale up and generate sustainable business growth. In doing so, the Fund would generate social and financial returns to drive inclusive economic growth in NSW and change the cultural misconceptions that marginalise women, especially disadvantaged women, from business. There is a significant opportunity for NSW to help many women small business owners unlock their potential and achieve economic security through contributing to the dynamism and growth of the wider economy. Moreover, the Fund would prioritise businesses which would create good jobs (well-paying, respectful, safe, secure, flexible, predictable hours, career-advancing, purposeful), compounding the social benefits of its capital outlays.

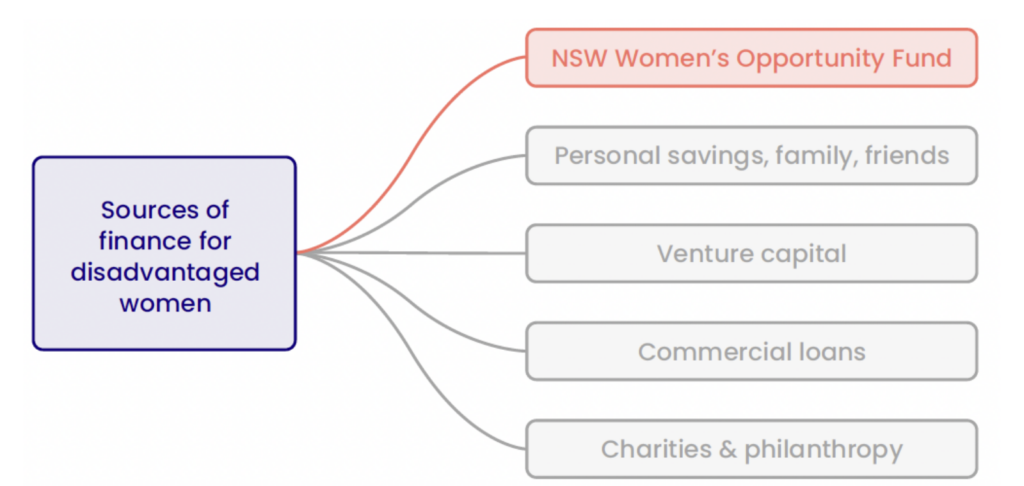

The Fund’s role is to address the gap in capital for disadvantaged women who own viable businesses with some growth potential, and to positively shape markets to better meet their needs. Other sources of finance – savings, existing venture capital, commercial loans – are not readily available to the Fund’s target cohort. The Fund would address this gap in the market by providing a greater choice and volume of finance to small business owners.

Helping disadvantaged women achieve business success

It is now widely known that women entrepreneurs tend to have less access to finance, and less awareness of funding options. Women who experience forms of disadvantage, in addition to that due to gender, face even greater barriers to growing their business. In the context of NSW, such women could include: Indigenous women; migrant or refugee women; women in rural, regional and remote areas; women from low income households or backgrounds; and women living with a disability. This policy brief suggests that the Fund initially target refugee women and/or women in rural, regional and remote areas under pilot schemes, before scaling up to include a broader cohort.

About this Policy Brief

Problem

Disadvantaged women face additional barriers to raising capital to grow their businesses

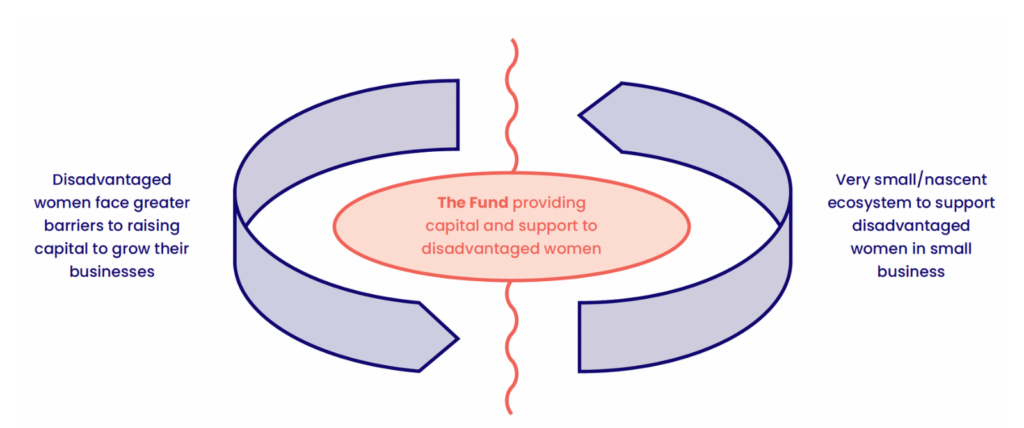

Figure 1: Disrupting a self-perpetuating cycle

Many women face additional disadvantages in, and have few options for, raising capital to grow their businesses

It is well understood that women in general face greater barriers than men in small business and entrepreneurship. Access to capital, networks and relevant education and skills are the most oft-cited barriers. Women in NSW from backgrounds that further disadvantage them in access to capital, networks, and skills will experience even greater barriers to success in small business. Such women could include:

- Indigenous women;

- migrant or refugee women;

- women in rural, regional and remote areas;

- women from low-income households or backgrounds; and

- women living with a disability.

Women who experience forms of disadvantage or marginalisation in addition to that caused by gender (e.g., racial discrimination, living with a disability, or lower income) face even greater barriers to growing their business. [1] Research on female entrepreneurs confirms this, showing that the more “counterstereotypical” an entrepreneur is, the greater the risk perceived by potential funders. [2] The further an entrepreneur deviates from the stereotype of a white middle-class man as the model of success, the more they will be scrutinised and harshly evaluated, while having to do more to prove their legitimacy and potential. [3] Moreover, female entrepreneurs who operate in industries, sectors or communities that funders are personally unfamiliar with are also regarded as greater risks. [4] Reflecting the greater barriers faced by women experiencing multiple forms of disadvantage, African American and Hispanic women in the United States have been shown to receive disproportionately low amounts of funding for their businesses. [5] While many of these findings pertain to venture capital ecosystems seeking to back high-growth ventures, the underlying dynamics largely hold true, and in some respects may be worse, for small businesses seeking growth at a low to moderate level.

While we can assume a similar situation in Australia, there is more limited research and data on the extent to which Australian women from disadvantaged backgrounds face greater barriers to raising capital. Nonetheless, it is clear that particular groups are at a significant disadvantage in raising capital – for example:

- Indigenous-owned enterprises which applied for investment from the Indigenous Social Enterprise Fund run by Social Ventures Australia struggled to meet the requirements and parameters for commercial lending. [6]

- Migrant and refugee women often require specific supports in entrepreneurship for various reasons, including: [7]

- language and/or cultural barriers;

- lack of savings and other financial capital;

- lack of credit and banking history in Australia;

- lack of local business experience and/or knowledge;

- needing to attend training during school hours when they are a primary caregiver;

- some women feel more comfortable learning and working with other women;

- some women have preconceptions about their capabilities and have a lack of self-confidence, especially if their partner is reluctant to have them work outside the home; and increased levels of discrimination.

- Women in regional, rural, and remote areas face particular difficulties due to their location, making access to finance difficult, as well as access to educational resources and networks. [8] For instance, women who work on a family farm may not have their own independent banking and finance, meaning banks are reluctant to lend directly to them. These women also often need flexibility to balance their own small business with caring responsibilities and farm work.

While entrepreneurship and small business are valuable means for women to become more financially empowered, it is important to also recognise that they are not appropriate for all people. [9] Running a small business successfully is enormously difficult and unpredictable. In order to maximise the chances of success for the enterprises it supports, the Fund should only be available to existing businesses that have a track record, or potential, of sustainable profits, and where capital would facilitate business growth.

The ecosystem to support disadvantaged women in business in Australia is very limited

Compounding and perpetuating the additional barriers faced by disadvantaged women is the relatively small ecosystem of social enterprises aimed at boosting their participation in small business and entrepreneurship (see Figure 1 above). As of October 2021, there were only nine early-stage development programs in Australia aimed at providing “opportunities for an economically marginalised community or group to engage in entrepreneurial activity.” [10] Not-for-profit organisations that operate in this space are predominately focused on providing advice in setting up a new business, rather than providing capital to help an existing enterprise to grow. Moreover, for refugee and migrant women, for instance, ventures and programs supporting entrepreneurship are largely confined to metropolitan areas and have very limited scope and scale. [11] Meanwhile, public and private sector social impact investing programs in Australia tend to focus on enterprises that demonstrate potential for innovation through, and significant social impact resulting from, their work. This is distinct from viewing economic security for women entrepreneurs from disadvantaged backgrounds as a social impact outcome in its own right.

Given the limited support ecosystem outlined above, there is a need for a fund that directly seeks to achieve social impact by providing disadvantaged women with capital and additional assistance to grow their businesses. By focusing on a broad base of conventional, slower-scaling small businesses, the Fund can stimulate economic growth for NSW while helping more women achieve greater economic security.

The NSW Women’s Opportunity Fund (“the Fund”) would be a Government-owned (but independently managed) Fund which crowds in private capital to provide suitable financial products and holistic business support to women small business owners who belong to disadvantaged groups or communities. The Fund would constitute a form of “social impact investing” because it aims to achieve a social objective (i.e., more women from disadvantaged backgrounds being successful in business) alongside a financial return (i.e., the growth of those businesses and financial returns for the Fund). [12]

The purpose of the Fund would be to provide capital and enable access to a range of additional supports, such as networks and upskilling, to help disadvantaged women grow their businesses. The Fund can also help its recipients link into the wider innovation ecosystem to enable them to effectively innovate in their small businesses (for example, through web design, export strategy or digitising operations).

The Fund would specifically target cohorts of women whose background or characteristics mean that they are systematically disadvantaged in accessing capital from mainstream or conventional sources and the array of supports that enable entrepreneurialism. Examples of such cohorts could include women from refugee or migrant backgrounds and women living and working in regional, rural and remote areas of NSW. The support for disadvantaged women to grow their businesses would constitute the core social objective of the Fund.

The Fund would integrate social and financial objectives, delivering long-term value for women small business owners as well as for the wider economy. By adopting a social impact investment framework – one which encompasses economic security and good jobs – the Fund would differentiate itself from other sources of finance available to women entrepreneurs. In particular, the Fund would have a willingness and capacity to take on certain levels and types of risk (for instance, when owners have few or no assets, or lack credit history), and to offer a degree of flexibility to its recipients, that reflects the lived realities of disadvantaged women in a range of circumstances. This kind of risk and flexibility would not typically be attractive to the commercial financial market. Moreover, beyond these financial considerations, there are often human and social barriers to accessing capital, with a lack of relatable and approachable financing options embedded in the disadvantaged communities where it is needed. Consequently, the Fund should be designed to facilitate ease of access end-to-end from initial application to the provision of ongoing support. The Fund’s operational effectiveness in connecting with, and relating to, women neglected by standard capital markets should be one of its distinguishing features.

The Fund could provide capital in different forms and combinations – concessional loans, equity investments, and grants – that would help women from disadvantaged backgrounds to grow their business. While public money would be needed to set up and anchor the Fund, there is significant potential to generate participation from private market entities. Mainstream financial market players, particularly banks, would have strong reasons to participate in the Fund: to build connections with potential future business clients, while also delivering on their corporate social responsibility objectives. The crowding in of private capital would amplify the Fund’s impact, enabling it to connect into mainstream capital markets in ways which could benefit the women involved and the wider NSW economy over time. Where there are organisations, such as not-for-profits (e.g., Thrive Refugee Enterprises, detailed further below), already providing similar financial products and services to disadvantaged women, the Fund could consider partnership arrangements with them. This could include directly funding a partner organisation to scale-up an existing program.

Enabling disadvantaged women to access capital will grow small businesses — building economic security and creating jobs

The Fund would aim to expand the ecosystem of successful and diverse businesses owned by women in NSW. Its focus is less on identifying innovative businesses with high growth potential, and more on supporting a large number of conventional small businesses owned by women to scale up and generate sustainable business growth. For example, the Fund could back a woman in a rural town with a small business to sell her products across NSW, or it could back a refugee woman in Western Sydney to digitise her accounting and hire an assistant so her translation business can take on more clients.

The Fund’s role is to address the gap in capital for disadvantaged women who own viable businesses with some growth potential, including low to moderate growth potential, and to positively shape market dynamics which could better meet their needs over time. Other sources of finance are not necessarily available to this cohort for various reasons (Figure 2): very limited personal savings; venture capital, because it is focused on innovation and high-growth sectors like technology; commercial loans, because they require a credit history and/or assets as collateral; and charitable donations and philanthropy are highly constrained and inconsistent in availability. The Fund would aim to address this financing gap by providing a greater choice and volume of finance.

Figure 2: Sources of finance for disadvantaged women

Figure 3: Theory of Change

The Fund would also be different from other finance sources in its willingness and capacity to take on risk, allowing it to offer flexibility to disadvantaged women that reflects their needs. For instance, disadvantaged women may not be able to grow their business in a linear way (e.g., due to caring commitments or other employment), or the capital provided by the Fund might be put to best use on non-direct business expenses (e.g., childcare that allows a woman to devote time to her business).

The Fund would aim to generate social and financial returns that not only help drive growth in NSW, but that also change the cultural misconceptions that contribute to the marginalisation of women from business (Figure 3). Globally, there is an estimated USD 1.7 trillion shortfall in access to finance for small businesses owned by women. [13] There is a significant opportunity for NSW to help women unlock their own potential, achieve economic security, and contribute to the dynamism and growth of the wider economy. The Fund could also positively contribute to the Government’s fiscal balance sheet, both through its direct financial returns and indirectly by helping generate a larger business tax revenue base.

Options

What could the NSW Women’s Opportunity Fund look like?

Design principles

- The Fund should be administered at arm’s length from government, with individual funding decisions made by qualified investment experts.

- The Fund and individual funding decisions should be subject to rigorous monitoring and evaluation, while at the same time not overburdening women entrepreneurs with administrative requirements. Moreover, the Fund would be premised on the fact that, as with venture capital broadly, not all small businesses will successfully grow.

- The Fund should have a financial goal of a reasonable return, rather than maximal one.

- The application process for the Fund should be as simple and accessible as possible (especially to English as a second language speakers).

- The Fund should seek to include private sources of capital to amplify its scale of impact, as well as to incorporate commercial acumen, expertise about business, and industry knowledge in funding decisions.

- The Fund can identify opportunities to link recipients into the NSW innovation ecosystem, to help them grow their small businesses (e.g., web design, export strategy or digitising operations).

- Leverage Government procurement where possible to provide commercial opportunities for businesses the Fund provides capital to.

Investment principles

- The Fund should only provide capital to existing businesses that have a record of profitability, or show strong potential of becoming profitable. The business should demonstrate how the capital would enable growth of the business.

- Adopt long-term “patient capital” funding settings that do not require immediate returns or repayments and allow businesses opportunity to scale.

- The Fund should be tolerant of disruptions in the women’s lives that could make consistent business operations and growth difficult (e.g., family and caring responsibilities; domestic violence).

- Funding should be provided on a flexible basis that facilitates its use for expenses not directly related to the business (e.g., childcare that allows women to undertake essential business activity).

- Prioritise businesses that have the potential to generate good jobs in the longer term, in particular for women (i.e., well-paying, respectful, safe, secure, flexible, predictable hours, career-advancing, purposeful).

- Prioritise businesses that aim to employ women (in addition to the owner).

- The Fund should not make investments in businesses which actively cause social or environmental harm, or which violate the NSW Government’s own ESG principles.

Overview

- The finance options and holistic support offered to women should be tailored to meet the specific needs of the target cohort(s).

- We suggest two potential cohorts for the pilot(s) based on existing research and models for supporting their entrepreneurship.

Identifying potential clients for the Fund

- The Fund should take a strategic approach to identifying potential clients. This should aim to generate a large quantity of applicants with a record of successfully operating a small business.

- In addition to open calls for prospective applicants, the Fund could partner with not-for-profits (NFPs) working closely with relevant target communities, leveraging their networks and cultural competence.

- For instance, a program like Ignite could provide a pipeline of initially successful businesses.

- Partner NFPs could: spread information about the Fund in diverse communities; help identify women who already have profitable small businesses and encourage them to apply; and help women complete the application process (e.g., to overcome language barriers).

This program facilitates business creation for a diverse range of people, with a focus on those from vulnerable communities, such as people from refugee and migrant backgrounds. It is focused on people looking to establish a small business or expand an existing one. Entrepreneurs are supported by Ignite facilitators, industry experts, and volunteers from local businesses, councils, chambers of commerce and other individuals who can share their business knowledge and skills. A 2017 evaluation of the program reported that 42% of male participants and 63% of female participants were running a profitable business in the medium-term following engagement with Ignite.

Pilot Option 1: Women in regional, rural and remote areas

Case for investment:

- There is widespread ambition amongst, regional, rural and remote women to contribute to their families and communities while also increasing their economic independence through entrepreneurialism by growing a small business.

- Women in remote or isolated areas regard running a small business as an important opportunity for building connections and generating income while also having the flexibility to work around family and community commitments.

- Regional, rural, and remote women looking to grow their businesses report needing only relatively small amounts of capital:

- 85% of women needing capital want $50,000 or less

- 50% of women needing capital want $10,000 or less

- Women in these areas report several barriers to achieving their entrepreneurial aspirations:

- access to finance given limited personal credit history and assets owned in their own right

- limited personal savings

- lack of skills and education relevant to business

- social attitudes deterring women from running their own business

- distance from networks and business infrastructure

Capital support options:

- Concessional and interest-free

- Government-backed loan guarantees.

- Equity investments for high-growth potential businesses.

- Microloans for specific training, education, travel or business assets, especially if available quickly

Pilot Option 2: Refugee women

Case for investment:

- Refugees are 1.75 times more likely to be entrepreneurs than Australian taxpayers generally.

- Female refugees earn a higher proportion of their income from their own business than male refugees and are much more likely to report income from their own business than men.

- Main industries for refugee entrepreneurs are: retail, health care and social assistance, construction and transport, postal and warehousing.

- Anecdotal information suggests that most refugee women would seek relatively small amounts of approximately $5,000 to $50,000 to grow an existing business enterprise.

- Despite high propensity for entrepreneurship, refugees face greater challenges – including:

- low levels of savings and other capital; lack of credit history and assets to use as collateral

- language barriers and low self-confidence

- lack of recognition of professional skills; difficulty acquiring business skills; lack of experience in Australian business contexts

- minimal social and professional networks and limited family and community support

Capital support options:

- Concessional and interest-free loans

- Government-backed loan guarantees

- Equity investments for high-growth potential businesses.

- Credit risk-assessments using alternate data as a substitute for traditional credit rating systems.

- “Trial” microloans for small amounts with short terms and frequent repayments to allow refugee women to test their business plan and repayment capacity while developing a credit history.

Overview

- The Fund should offer a mix of financial products – equity investments, (concessional) loans and grants – that could be offered in combination and tailored to the specific needs of the women entrepreneurs and small business owners. Equity investments should be limited to well-established enterprises with strong potential for substantial growth; loans and grants would be most appropriate for small conventional businesses looking to achieve modest growth. Funding should be contingent on an existing record of profitability and a business case for how the capital will enable sustainable growth.

- The Fund, at least initially given its target market and small scale, would require public funding in its entirety in order to anchor the capital base. Over time, however, solid financial returns from this initial public investment could attract private investors. Partnering with a private finance provider, such as banks, to co-contribute capital with a government guarantee could be a viable option.

- The Fund should have a high degree of flexibility in the size and term of the financial products it offers women. Small amounts (e.g., up to $10,000 repaid over 6-12 months) could be offered alongside larger products up to several hundred thousand dollars. Capital could be provided in relation to specific activities, such as training, for general purposes, or to help women establish a favourable credit score.

- The Fund should seek to continuously review, iterate, and improve its financial products to maximise their impact for women entrepreneurs.

- Examples provided below demonstrate existing models for providing capital on a similar basis.

Overview

- Holistic support for women entrepreneurs, in addition to capital, is essential. Capital provided by the Fund should be accompanied by wraparound supports tailored to the circumstances of the women.

- The Fund should partner with not-for-profits who already work with relevant groups of women to deliver this support. This will help make services as relevant and effective as possible.

- Types of support that could be offered: education and training, networks, mentorship, business services (e.g., tax, accounting, legal, compliance), language and cultural support.

- Support services should be accessible to women in terms of location and cultural fit. Women should be able to receive these services without travelling far and in a supportive environment.

- There is a wealth of examples of incubators and start-up hubs to draw from. The below are a selection of especially relevant examples.

Endnotes

- Hyeun Lee and Sarah Kaplan, Gender, race, & entrepreneurship: Current understandings and a future research agenda, Women Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub, Institute for Gender and the Economy, 2021; Alison Rose, The Alison Rose Review of Female Entrepreneurship, UK Government, 2021.

- While there is limited existing research on the extent to which women from disadvantaged backgrounds in Australia can access finance for small business, research from the United States on capital-raising for businesses owned by social minorities is instructive here. Siri Chilazi, Advancing gender equality in venture capital, Harvard Kennedy School, 2019.

- Siri Chilazi, Advancing gender equality in venture capital, Harvard Kennedy School, 2019.

- Siri Chilazi, Advancing gender equality in venture capital, Harvard Kennedy School, 2019.

- Increasing venture capital to women-led businesses, Global Impact Investing Network; Siri Chilazi, Advancing gender equality in venture capital, Harvard Kennedy School, 2019.

- Indigenous Social Enterprise Fund: Lessons Learned, Social Ventures Australia, 2016.

- Philippe Legrain and Andrew Burridge, Seven Steps to Success: Enabling Refugee Entrepreneurs to Flourish, Centre for Policy Development, 2019; Jock Collins, Final Evaluation Report on the SSI Ignite Small Business Start-Ups Program, Settlement Services International, 2017; Swati Mehta Dhawan, Financial Inclusion of Germany’s Refugees: Current Situation and Road Ahead, European Microfinance Network, 2018.

- The economic security of women in rural, regional and remote Australia: Challenges, Opportunities and Optimism, THE Rural Women and economic Security4Women (eS4W), 2021.

- Scott Shane, ‘Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy’, Small Business Economics, 2010; Magnus Henrekson and Dan Johansson, ‘Gazelles as job creators: a survey and interpretation of the evidence‘, Small Business Economics, 2010.

- Libby Ward-Christie, Amber Earles and Michael Moran, Australia’s Social Venture Ecosystem: Understanding the Support and Development Landscape, Paul Ramsay Foundation, 2021.

- Philippe Legrain and Andrew Burridge, Seven Steps to Success: Enabling Refugee Entrepreneurs to Flourish, Centre for Policy Development, 2019.

- Social Impact Investing Taskforce, Social Impact Investing Taskforce: Interim Report, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2019.

- Increasing venture capital to women-led businesses, Global Impact Investing Network.