Executive summary

We have a problem with our gender pay gap in Australia. This policy brief considers innovative ways that existing government data can be unlocked, leveraged, and mobilised to enhance the performance of private sector employers towards closing the gender pay gap in New South Wales (NSW).

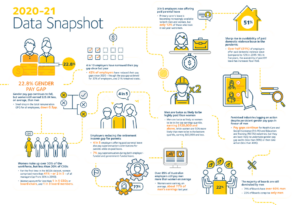

In 2021, Australia moved down six places in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index rankings to 50th place. [1] Our gender pay gap also worsened, increasing from 20.1 per cent in 2019-20 [2], to 22.8 per cent in 2020-21. [3] This is partially attributable to the economic effects of COVID-19, and the disproportionate disruptions experienced by female-dominated industries. [4] However, the gender pay gap has remained stubbornly constant in Australia, floating around the 20 per cent range since 2016. [5]

The NSW Government’s Women’s Economic Opportunities Review, provides a unique opportunity to consider innovative approaches to addressing gender inequity and enhance female economic participation, for the benefit of all. Simultaneously, the Commonwealth Government has undertaken a review of the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012. Amongst other reforms, the Commonwealth review has recommended the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 be amended to allow the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) to publish gender pay gap information at an employer level. [6]

While this policy brief focuses on private sector workplaces, we note that much of the report is also relevant to public sector organisations. Moreover, as a significant employer in NSW, there may be legitimate reasons for ensuring that the public sector is included to ensure the integrity and impact of the measures proposed.

About this Policy Brief

This policy brief proposes four key actions for the NSW Government to consider:

1 The NSW Government, in partnership with WGEA, should engage with private and public sector job search platforms to display an Employer of Choice for Gender Equality (EOCGE) citation “badge” on job ads for relevant NSW employers.

2 The NSW Government, in partnership with WGEA and other gender equity organisations, should invest in an information and advocacy strategy to increase the prominence and recognition of the WGEA EOCGE citation, and drive uptake among NSW employers.

3 The NSW Government should consider investing in randomised control trials on how best to advance commitments to gender equity in NSW workplaces, including practical insights on how best to influence key decision-makers in firms.

4 The NSW Government should work closely with the Commonwealth Government to ensure that WGEA data on individual organisations’ gender pay gap be made publicly available (aligned with the recommendation from the Workplace Gender Equality Act Review).

World-leading data is already available to be unlocked

There is a significant opportunity for the NSW Government, in partnership with WGEA, to leverage the existing world-class data that WGEA captures on workplace gender equity and drive meaningful change on the gender pay gap within NSW.

In addition to the data that WGEA collects as part of their Compliance Reporting Program (mandatory reporting on gender equity for organisations of 100+ employees), the Agency also administers the EOCGE citation. The citation is a voluntary leading practice recognition program designed to encourage, recognise, and promote organisations’ active commitment to achieving gender equality in Australian workplaces. [7] The citation is awarded to organisations that can demonstrate they have policies, procedures, and practices in place to address the various determinants of gender inequality. Of the 4,474 organisations that were required to report under the Compliance Reporting Program in the 2020-21 reporting period, only 130 have received the EOCGE citation. [8] The Workplace Gender Equality Act Review has also recommended that WGEA review EOCGE citation to improve its effectiveness and uptake. [9]

Further details on WGEA’s Compliance Reporting Program, the EOCGE citation, and details of a recent study undertaken into the effects of the EOCGE citation are included in Appendix A.

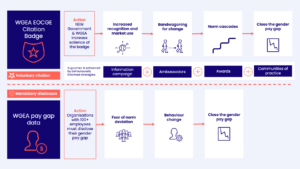

The NSW Government can leverage behavioural insights to drive change on the gender pay gap

The NSW Government should identify effective ways to enhance awareness and market recognition of the existing WGEA EOCGE citation, including through its incorporation as a “badge” in job advertisements. The NSW Government, in partnership with WGEA, could work collaboratively with private sector job search platforms – who are ready and willing to engage – to achieve this. Through enhanced market recognition, more employees will seek evidence of the citation from prospective employers during the job search process. Increased recognition of the citation badge in the market could create a “bandwagoning effect” whereby more organisations seek to apply for the EOCGE citation. This could lead to a “norm cascade”, driving up commitments and behaviours on gender pay equity across companies in NSW.

The NSW Government could also mandate individual organisations to disclose their gender pay gap performance. This would ideally align with potential reforms at the Commonwealth level, though NSW should be prepared to lead if change at the federal level stalls. Employers’ fears and anxieties associated with public exposure of poor performance, as well as being outliers, or “norm non-conformers”, could encourage more employers to take action to close their gender pay gap. Mandatory disclosure rules could be supplemented, over time, with financial enforcement measures, such as fines or additional taxes, as well as exclusions from government procurement panels for non-compliant organisations.

A summary of the proposed approach is captured in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Summary of proposed approach

To maximise the likelihood that organisations will take action to address the gender pay gap, and indeed gender equity more broadly, a combination of both approaches would maximise impact. Influencing voluntary behaviours will likely have a greater impact on changing attitudes and beliefs over time, and influencing behaviour through mandates will accelerate the speed of change and force laggards to take action.

By encouraging increased EOCGE citation, the NSW Government can influence organisations to close the gender pay gap.

For the EOCGE citation to work as a nudge, it needs to be effectively integrated into the labour market

Currently, prospective employees need to search for the EOCGE citation on individual company websites, requiring them to know it is available. To enhance its prominence in the market, the WGEA EOCGE citation badge could be made available for inclusion on job ads on private sector job search platforms, such as Seek and LinkedIn, as well as on government recruitment portals. Over time, employees will come to recognise the EOCGE citation badge, and begin to search for it in job ads and on employer websites.

Labels for energy efficiency or fuel economy, “nutritional facts” panels on food, or cigarette package warnings are all examples of behavioural “nudges” for communicating specific information to consumers, in order to influence their choices and behaviour, to enhance welfare. To be effective, nudges need to be designed in such a way so as to make choices simpler and easier for people to navigate. [11] In particular, nudges that increase the ease and convenience of decision-making can be very effective where the amount of information is vast, complex, or not accessible/digestible by end-users who are making decisions. [12] Additionally, mechanisms for disclosure of this complex information can also help decision-makers make better informed choices based on improved accessibility of data. [13]

The WGEA EOCGE citation is an existing governmental tool which enables public communication and disclosure of an organisation’s commitment to gender equity. In addition to being a mechanism for encouraging employer good practice, it also serves as an easily recognisable market signal, or label, to current or prospective employees, informing them of an organisation’s gender equity commitment.

In a report by Work180 titled What Women Want 2021: A global report revealing what women want and need to thrive in the workplace, 91 per cent of respondents agreed that it is valuable to be able to easily identify organisations that are considered to be “great employers for women”. [14] Additionally, an overwhelming 93 per cent of respondents indicated that they want to know what benefits and policies an employer offers before applying for a role with them. [15]

As market recognition increases, a bandwagon effect can drive normative change

As the recognition of the WGEA EOCGE increases among employees, it is reasonable to assume that more and more employees will look for this indicator of gender equity performance in an employer. Similarly, as more and more employers adopt the citation, a trend is likely to emerge among employers. Over time, the EOCGE citation could become an employment market norm, and a well-recognised signal of employer “good practice”.

A VicHealth report, Framing gender equality: Message Guide, surveyed individuals’ attitudes towards gender equality. The report identified that:

- 25 per cent of respondents fell into the “supporter” category;

- a majority 60 per cent of respondents fell into the “persuadable” category; and

- only 15 per cent identified as “opponents”. [16]

There is clearly a significant opportunity to shape the opinions, beliefs and importantly motivations of the 60 per cent that can still be persuaded about the importance of gender equity.

In the context of workplace gender equity, leading organisations, or “supporters”, are already aware of the market benefits of obtaining the EOCGE citation. CEOs of “first mover” organisations with a WGEA EOCGE citation recognise that there is a strong commercial driver to being a citation holder because it provides good public recognition of an organisation’s focus on gender equality. [17] They claim the citation supports their ability to attract and retain the best possible talent to build a high-performance workforce. This provides a significant differentiation in a competitive marketplace. [18]

As the WGEA EOCGE citation becomes more widely adopted, and the citation becomes prominent in the labour market, it is reasonable to assume that a “bandwagon effect” could take effect among employers and employees. The “bandwagon effect” describes a phenomenon by which public opinion or behaviours shift due to particular actions and beliefs gaining momentum amongst the public. [19] Put simply, people are more likely to adopt behaviours as the proportion of others who have already done so increases. [20] This is particularly true of organisations, and their leaders, who might fall into the “persuadable” category. There is potential in NSW for a kind of “positive bandwagon effect” as more organisations emulate the good practices of their more gender equitable peers.

Bandwagoning can eventually lead to a “norm cascade”, [21] to shift collective behaviours towards improved gender equity outcomes. This could be especially powerful for “persuadable” organisations or leaders, which in turn raises social and normative expectations on laggards (or “opponents”) to improve their performance.

NSW Government can mobilise and enhance market recognition of good performers

A key goal should be to establish the WGEA EOCGE citation as a widely recognised, credible common standard in NSW, one that can be used confidently by employers and employees alike to inform their choices and signal their commitments. Private sector firms seeking to improve gender equity performance in workplaces would then be able to support companies to achieve, and even exceed, the WGEA standard.

There are two key roles for the NSW Government to play in order to enhance the recognition of the WGEA EOCGE citation and also to further encourage uptake of the citation by NSW employers.

1. Enhancing the mechanisms for communication of the EOCGE citation

By working in close partnership with WGEA, the NSW Government can enable collaborations with private sector job search platforms, such as Seek, LinkedIn and others, as well the NSW Government recruitment portal, I work for NSW. By working with these platforms, the government can encourage them to display the WGEA EOCGE citation logo as a badge on relevant job ads for cited organisations. In addition to the badge being displayed in job ads, the NSW Government and WGEA can engage with NSW citation holders to encourage them to display their citation clearly and prominently on their website.

By increasing the prominence of the citation in this way and making it more accessible for prospective employees, the Government can enhance the behavioural effect of the citation and support more informed choices.

Recommendation 1

2. Government information campaign and advocacy efforts

Government can amplify and accelerate the EOCGE citation’s impact through the following additional initiatives:

Recommendation 2

All of the initiatives suggested in this section are grounded in the behavioural insights literature as effective mechanisms for nudging behaviours and encouraging voluntary actions. However, some policies, including some nudges, may not be as effective, or could even fail in practice. Empirical tests, including randomised controlled trials, will be important for assessing what works to change behaviour and drive equitable outcomes inside businesses. [24]

Recommendation 3

Transparent reporting of WGEA data can accelerate closing the gender pay gap

Mandatory and transparent disclosure of gender diversity performance could encourage voluntary behaviour change

Mandating disclosure of certain measures or outcomes is another behavioural mechanism, or nudge, that can influence behaviours, both for employees and employers. [25] When these disclosures demonstrate than an actor is outside of a social norm, or not performing as well as their peers, this can act as a further incentive to take action.

Social norms are sustained by the feelings of embarrassment, anxiety, guilt, and shame that individuals suffer at the prospect of violating them. [26] Because violations of social norms create such negative feelings, they impose costs on those who violate them. [27]

Therefore, mandating the disclosure of an individual organisation’s gender pay gap data, a metric that is currently kept confidential by WGEA and shared only with each respective organisation in a confidential report, could have a significant effect on an organisation’s desire to stay aligned with social norms, or at the very least, to not be at the bottom of the pack. The Workplace Gender Equity Act Review has recommended this change to WGEA gender pay gap reporting.

By collaborating with the Commonwealth Government on this measure, the NSW Government could significantly influence employer behaviour. If reforms at the Commonwealth level were to stall, then the NSW Government should consider mandating disclosure of this data at a state level.

By indicating an appropriate lead-in time before this data will be publicly disclosed, organisations would have an opportunity to take action on gender equity broadly, and their gender pay gap specifically, before their performance was made public. In this time period, it is likely that a significant number of organisations would seek to make progress on their gender pay gap, in order to not appear to be outside of social norms on employer performance for this indicator.

For employers that are already EOCGE citation holders, and are already leading on gender equity within their workplaces, they might be encouraged to further improve their performance, or accelerate strategies they have already developed, or make significant innovations in their approach to addressing gender equity, that could be modelled by others.

Recommendation 4

The NSW Government could implement varying degrees of enforcement tied to mandatory disclosure

If mandatory gender pay gap data disclosure is introduced for all NSW employers that already need to report to WGEA under the Compliance Reporting Program, the NSW Government could consider additional mechanisms for ensuring enforcement, in addition to behavioural incentives. Any additional mechanisms would need to be considered in light of any reforms introduced at the Commonwealth Government level.

Building on the experience in other OECD jurisdictions (explored further in Appendix B), the NSW Government could consider introducing financial penalties or other costs for employers who either do not comply with their reporting and disclosure requirements, or who persistently do not demonstrate improvement against their gender pay gap metrics. These could take the form of:

If such penalties were to be introduced, it is important that they are not perceived as simply another cost of doing business, thereby disincentivising an organisation’s potential commitment to gender equity. Further work would need to be done on the optimal strategy for combining behavioural interventions and imposing costs.

Appendices

Endnotes

[1] Global Gender Gap Report 2021 Insight Report, World Economic Forum.

[3] WGEA Data Explorer, WGEA.

[4] COVID-19 and gender equality: Countering the regressive effects, McKinsey & Company.

[5] Australia in Context: Country Comparison of Gender Performance, Women NSW.

[6] WGEA Review Report, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Commonwealth Government has been working towards implementation of the report’s recommendations, noting that the report requires further consultation with business on some aspects. See Senator the Hon Marise Payne, Media Release: Review of Workplace Gender Equality Act Report.

[7] Employer of Choice for Gender Equality, WGEA.

[8] WGEA Data Explorer, WGEA; Employer of Choice for Gender Equality, WGEA.

[9] WGEA Review Report, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

[10] The gender pay gap measures the difference between the average earnings of women and men in the workforce. The gender pay gap is the result of the social and economic factors that combine to reduce women’s earning capacity over their lifetime. Closing the gender pay gap goes beyond just ensuring equal pay. It requires cultural change to remove the barriers to the full and equal participation of women in the workforce. It is for this reason that throughout this report, we have referred to actions to address gender equity more broadly, as such measures will also have impact on the pay gap.

[11] Cass R. Sunstein, How Change Happens, MIT Press, 2019, p. 60.

[12] Cass R. Sunstein, How Change Happens, MIT Press, 2019, p. 63.

[13] Cass R. Sunstein, How Change Happens, MIT Press, 2019, p. 63.

[16] Framing Gender Equality: Message Guide, 2021, VicHealth.

[17] EOCGE Application for New applicants, 2021-23, WGEA.

[18] EOCGE Application for New applicants, 2021-23, WGEA.

[19] Rüdiger Schmitt‐Beck, ‘Bandwagon Effect’, in Gianpietro Mazzoleni et al (eds.), The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication, Wiley Blackwell, 2015, pp. 57-61.

[20] Andrew Colman, Oxford Dictionary of Psychology, Oxford University Press, 2014.

[21] Cass R. Sunstein, ‘Social Norms and Social Roles‘, Columbia Law Review 903, 1996, pp. 903-968.

[22] Iris Bohnet, What Works: Gender Equality by Design, Harvard University Press, 2016.

[23] Cass R. Sunstein, How change Happens, MIT Press, 2019.

[24] Iris Bohnet, What Works: Gender Equality by Design: Drivers and contexts of equal employment opportunity and diversity action, Harvard University Press, 2016.

[25] Cass R. Sunstein, How Change Happens, MIT Press, 2019, p. 63.

[26] Cass R. Sunstein, How Change Happens, MIT Press, 2019, p. 7.

[27] Cass R. Sunstein, How Change Happens, MIT Press, 2019, p. 7.

[28] Welcome to WGEA, WGEA.

[29] Employers with less than 100 employees, or public sector organisations (i.e. not “relevant employers” under the Act) can still voluntarily submit reporting data to WGEA.

[30] Reporting, WGEA.

[31] Australia’s gender equality scorecard, WGEA.

[32] What are the minimum standards for organisations with over 500 employees? WGEA Employer Portal.

[33] Non-compliant organisations list, WGEA.

[34] Employer of Choice for Gender Equality, WGEA.

[35] Employer of Choice for Gender Equality, WGEA.

[36] EOCGE Application for New applicants, 2021-23, WGEA.

[37] Employer of Choice for Gender Equality Leading Practices in Strategy, Policy and Implementation, AIBE Centre for Gender Equality in the Workplace.

[38] Employer of Choice for Gender Equality Leading Practices in Strategy, Policy and Implementation, AIBE Centre for Gender Equality in the Workplace.

[39] Employer of Choice for Gender Equality Leading Practices in Strategy, Policy and Implementation, AIBE Centre for Gender Equality in the Workplace.

[40] Global Gender Gap Report 2021 Insight Report, World Economic Forum.

[41] Data provided by Women NSW.